Thirty years ago this summer, 30 miles south of the Canadian border, gunfire erupted on an Idaho mountainside in an awful showdown that devastated a frontier family and scarred the nation. Three people died in the shootout that became known as Ruby Ridge—a mother, her 14-year-old son and a federal marshal—and two others were wounded.

The attacks and ensuing Senate hearings undermined public faith in the government and forced federal authorities to reconsider their “rules of engagement” in crisis situations.

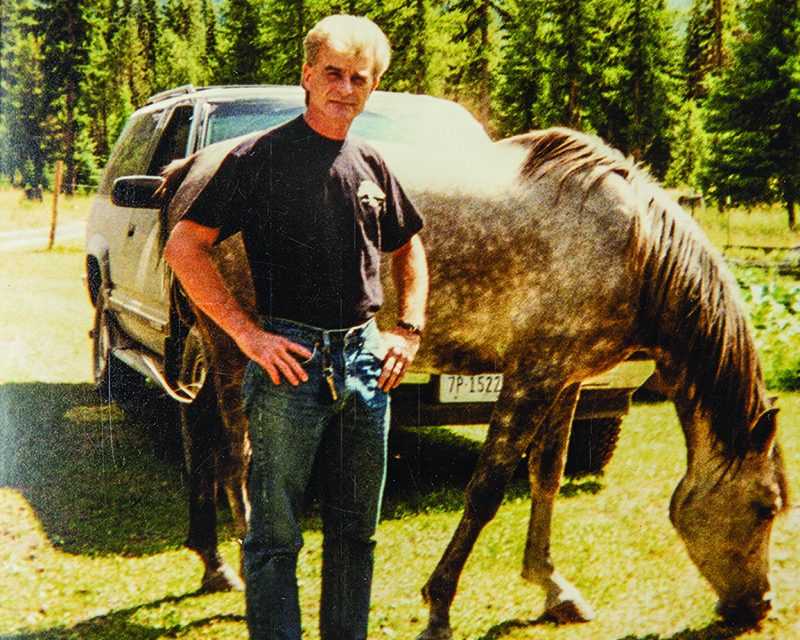

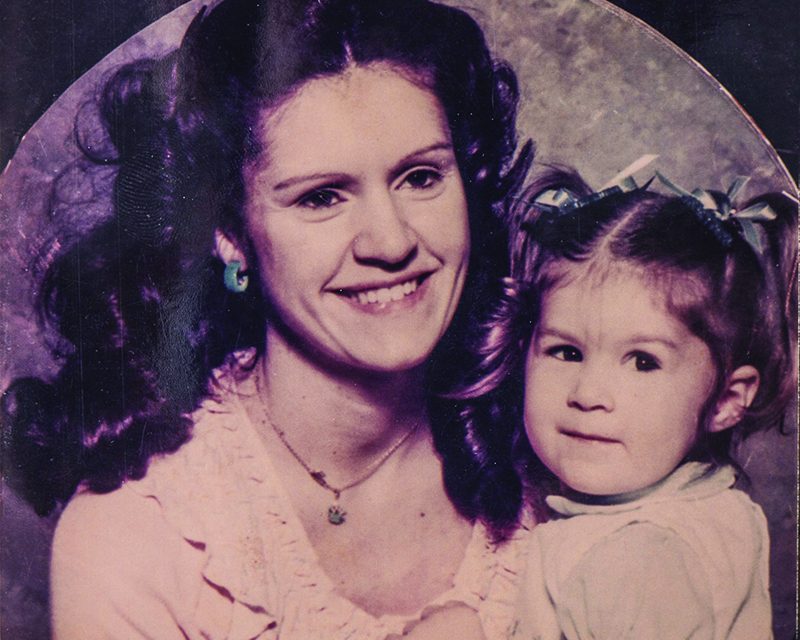

“We were a typical Midwestern family,” said Sara Weaver, who was 16 at the time her family was in the crosshairs of federal snipers. Her grandparents were farmers in Fort Dodge, Iowa. Her father, Randy, served in the Army as a Green Beret and worked as a tractor mechanic in Cedar Falls. Her mother, Vicki, was a stay-at-home mom. Sara had a younger brother, Sam, and also a younger sister.

The family attended church, and Sara memorized John 3:16, a verse that stuck in her heart and would bring her to salvation 20 years later. But when she was 7, there was a division in the church, and the congregation split, with half the members leaving, including the Weavers. In Sara’s teen years, her parents became preoccupied with Old Testament law, particularly the Ten Commandments.

“Mom and Dad said we were a family who wanted to please God,” Sara wrote in her book, “Ruby Ridge to Freedom.”

Randy and Vicki, concerned about what they perceived as the decline of American society and a coming apocalypse, decided to move to the relative security and serenity of the Rocky Mountains. “We wanted to be separated from the rest of the world,” Randy said in a 2020 Fox interview. “Survival, you might call it. We wanted to separate out and be able to survive any bad times ahead.”

The Weavers intended to live off the grid in Idaho, where they could homeschool their children, which was not permitted in Iowa.

Randy purchased 20 wooded acres on Ruby Ridge and used sawmill scraps to build a cabin. Vicki sold her wedding ring to pay for the roof. They had never built a house before, and Randy joked that it probably wouldn’t last five years. They hauled water from a spring, cooked on a wood stove, and used an outhouse.

The family often lived on less than $100 a week. Randy did odd jobs and sold firewood, the children collected and sold huckleberries, and Vicki “could stretch a nickel into a dime,” as the family said. Vicki was also the home- school teacher for Sara, Sam and Rachel. Sara gained a big brother when her parents took in a runaway teen named Kevin Harris.

At one point, a friend invited the family to attend a camp known as Aryan Nation, Church of Jesus Christ Christian. “There was nothing Christian about it, and I definitely never met Jesus Christ there,” Sara said. The Aryan Nation was a white supremacist group that was militantly antigovernment and was later labeled by the FBI as a terrorist threat.

Their quiet world started to unravel in 1989, when a man named Gus asked Randy to illegally alter two shotguns. Randy had known Gus for three years, and finally agreed to do so for a price. In January 1991, Randy and Vicki stopped to help a broken-down truck. “Before they knew what was happening, they were facedown in the snow and mud, with guns trained on them, being frisked by ATF agents who had been hiding in the back of the truck,” Sara wrote. One of the agents told Randy he knew about the illegal work he had done on Gus’ shotguns. It turned out that Gus was an undercover agent. It had been a setup from the beginning.

The agents offered to drop all charges if Randy would become an informant for the Aryan Nation, but Randy refused to become a “snitch.” Randy and Vicki were handcuffed, and Randy was put in jail, Sara wrote.

That ambush started a series of events that led to the Ruby Ridge shootout. “It would go down in history as one of the most tragic and shameful events in the history of our great country,” Sara wrote. After Randy missed a court date, Sara heard on the radio that her father “was considered to be like a wild animal in the mountains, and that U.S. marshals would bring him in.”

The Weavers never left the mountain for any reason, Sara wrote, not even for Vicki to give birth to her fourth child, a baby girl. Randy delivered the infant in a guest house beside their cabin. The baby was 10 months old in August 1992. On the morning of Aug. 21, the family dogs became restless as if there might be coyotes prowling nearby. Randy, Sam, Kevin, and a yellow lab named Striker went to investigate.

“Suddenly, I heard a gunshot,” Sara wrote. “My heart dropped to my stomach.” After more shots, she heard her father yelling, “They shot Striker! Sam! Kevin! They shot Striker.”

What exactly happened down the hill from the cabin? Accounts differed, and the Department of Justice and a Senate Judiciary subcommittee, chaired by Sen. Arlen Specter, had to sort through conflicting details and perspectives.

This much is certain. Six U.S. marshals, camouflaged and masked, were sent to Ruby Ridge on Friday, Aug. 21, 1992, to arrest Randy Weaver for failing to appear in court. Randy came down one trail and retreated when a marshal ordered him to halt.

A moment later, Sam, Kevin and Striker emerged from another trail, unaware that they were walking into a trap. One of the marshals shot the barking dog. Sam reacted like a 14-year-old might after seeing his dog killed: He fired three shots in anger, and then retreated uphill as he heard his father calling—only to be shot in the back by one of the marshals. Kevin, 24, fired his rifle into bushes where Marshal Bill Degan was hiding. Degan was killed during the shooting, but it was never proven who shot him. Investigators said of the 19 shots fired that day, the first seven were from Degan.

That afternoon, Randy, Vicki and Kevin retrieved Sam’s body and laid him in a guest house next to the cabin.

Overnight, the FBI mobilized a military-scale operation in the meadow below the Weavers’ cabin. The agency flew in its specially trained hostage rescue team from Quantico, Virginia, and positioned sharpshooters on knolls near the cabin.

During the flight from Virginia, agents scribbled out the “rules of engagement.” Essentially, the FBI decided to take Randy Weaver dead or alive. Sharpshooters had these orders: “If an adult in the compound is observed with a weapon after the surrender announcement is made, deadly force can and should be employed to neutralize the individual.”

The Weavers did not know they were surrounded, and on Saturday, Randy, Sara and Kevin went to the guest house to pay their respects to Sam. As Randy raised his arm to unlatch the shed door, a gun was fired, hitting him in the shoulder. As Sara and her father ran toward their house, she followed closely behind him in an attempt to block the sniper’s line of fire. She thought to herself, If you want to murder my dad, you’re gonna have to shoot another kid in the back first.

Vicki, with her baby in her arms, was holding the door open. From a distance of 200 yards, the sniper fired at Kevin as he entered the doorway, and the bullet tore through the door, killing Vicki and wounding Kevin in the ribs.

For more than a week, the surviving Weavers were under siege, barricaded in their blood-splattered house with the curtains closed while the children tended to the wounded men.

Day after day, agents on loudspeakers demanded surrender, but the Weavers feared that if they stepped outside, they would be shot. As anti-government protesters gathered at the Weavers’ gate, a local TV reporter commented: “Randy Weaver has told friends all he wants is to be left alone. But with the sudden appearance of military hardware like this, his one-man stand against the law is taking on the appearance of a full-blown war.”

Negotiators didn’t know Vicki was dead, and they aggravated the tensions by appealing to her over the loudspeaker: “Good morning, Mrs. Weaver, how are you doing today? How’s the baby? We had pancakes for breakfast; what did you have?”

Authorities even sent a robot to the cabin porch. The robot played recorded messages from radio commentator Paul Harvey and Vicki’s parents imploring the Weavers to pick up the robot’s phone. They suspected the robot was booby-trapped, and indeed they later discovered it was rigged with a sawed-off shotgun—the same type of weapon that Randy was accused of illegally selling.

“All signs pointed to an overwhelming conclusion that this was the end for us,” Sara wrote. “We knew no one was coming to the rescue. No one wanted to talk. They had made that loud and clear to us. I was sure that any minute, the rest of us would be murdered. I prayed for mercy, that they would just firebomb our house and get it over with all at once. I couldn’t watch the rest of my tattered and broken little family die.”

Finally, on Sunday, Aug. 30—nine days into the standoff— another former Green Beret named Bo Gritz negotiated a peaceful ending. First, he persuaded Kevin to surrender so he could get life-saving medical attention, and he also carried out Vicki’s body. The next day, Randy and his girls bravely exited their cabin and walked down their driveway into federal custody, re-entering a world where they had become symbols of defiance and heroes of survivalists.

Randy Weaver was charged with accessory to murder, conspiracy, assault and other crimes. He and Kevin were tried in 1993 in a federal court in Boise, Idaho. Their trial coincided with another spectacle of government heavy-handedness—the federal assault near Waco, Texas, that killed 82 civilians at David Koresh’s Branch Davidian church compound. In that context, defense attorney Gerry Spence persuaded the jury that Randy acted in self-defense, while accusing authorities of “criminal wrongdoing.”

The jury deliberated for 20 days and acquitted Randy on all charges except failing to appear in court, for which he served 16 months in prison. Randy Weaver died earlier this year at age 74. Kevin Harris was acquitted of all charges.

The sniper who killed Vicki Weaver was indicted for manslaughter, but charges were dropped.

Spence sued the federal government on behalf of the family and won a cash settlement. The daughters each received $800,000. “It was blood money, in my eyes,” Sara wrote. “It haunted me that this was the price placed on Mom and Sam.”

The government did not apologize in the 1995 civil settlement with the Weavers, but FBI Director Louis Freeh admitted fault when he testified before the Senate subcommittee: “Ruby Ridge has become synonymous with tragedy, given the deaths there of a decorated deputy United States marshal, a young boy and the boy’s mother. It has also become synonymous with the exaggerated application of federal law enforcement. Both conclusions seem justified.”

Randy was not called to testify at his trial in Idaho but did speak to a Senate Judiciary subcommittee in 1995: “If I had it to do over again, I would have come down from the mountain for the court appearance,” he said. “I would not have allowed a deceitful, lying con man working for BATF [Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms] to push me to make a sawed-off shotgun for him. I would not have allowed myself to be tempted in a weak moment when my family needed money. But my wrongs did not cause federal agents to commit crimes. Nothing I did caused federal agents to violate the Constitution of the United States.”

Freeh admitted that the FBI exaggerated the threat posed by Randy Weaver: “The FBI did not perform at the level which the American people expect or deserve. Ruby Ridge was a series of terribly flawed law enforcement operations with tragic consequences.” Freeh said the death of Vicki Weaver “will always be a haunting reminder to the FBI to take every possible step to avoid tragedy, even in the most dangerous situations.”

The Justice Department determined that the rules of engagement were confusing and unconstitutional.

In the following years, Sara and Randy told their story in a series of public appearances. Most important, as she dealt with the trauma of Ruby Ridge, Sara came to saving faith in Jesus Christ and was able to forgive the agents who massacred her family. On the following pages, she shares her testimony of how she was “radically saved.”

Tom Layton is print editor for Samaritan’s Purse.

Above: Sara Weaver sits on the swing outside the house at Ruby Ridge.

Photos: Courtesy of Sara Weaver