In early January 2018, along some of the main thoroughfares in Greater Cleveland, billboards that espoused the “benefits” of abortion began popping up. The signs, placed by Ohio’s largest abortion business, Preterm, carried messages such as “Abortion is sacred,” “Abortion is a family value,” “Abortion is safer than childbirth” and “Abortion is a blessing.” It was all part of the group’s “Abortion is” campaign to reduce abortion stigma.

The billboards stood in some of Cleveland’s poorest neighborhoods, their bold and ironic claims plainly contradicting Scriptural teaching about the inherent value of human beings made in God’s image (Genesis 1:27; Psalm 139:13-15).

These billboards caught the attention of Franklin Graham. He posted on Facebook, Jan. 4, 2018: “God says, ‘Woe to those who call evil good and good evil.’ That’s exactly what an abortion business in Ohio is doing. … These are all lies. Here’s a billboard for them—’Abortion is evil, because it’s murder.’ Pray that America will wake up to the tragedy of children being killed through abortion every day in this nation.”

Long before the campaign launched, black pro-life groups and civil rights leaders had been exposing the chilling aspect of such morbid propaganda efforts: The abortion industry disproportionately targets African-Americans. In fact, many black pro-life leaders have a bold term for it: black genocide.

In Cleveland, pro-life leaders saw the same disproportionate marketing of abortion to African-American areas. But right-to-life activists weren’t the only ones who noticed.

“You know when local grassroots activists from the NAACP and Al Sharpton’s National Action Network agreed with right-to-life and pregnancy center directors, the racial targeting was obvious to everyone,” says Ryan Bomberger, a prominent pro-life speaker and activist and chief creative director of The Radiance Foundation, a “life-affirming” organization he began with his wife, Bethany.

For Bomberger, the issue is personal: He is biracial (black biological father, white biological mother), was conceived in rape and adopted into a multiracial Christian family with nine other adopted siblings. He and his wife are adoptive parents.

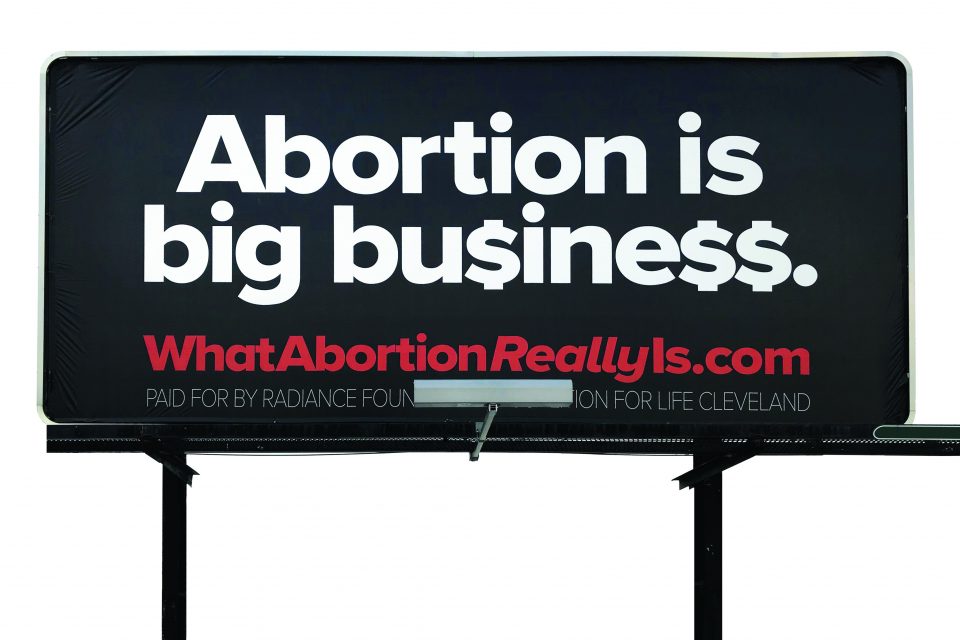

After the Cleveland billboards appeared, The Radiance Foundation, along with Coalition for Life Cleveland, started a billboard campaign of their own, dubbed “What Abortion Really Is.” The billboards went up in February 2018, during Black History Month, although about half of them, with messages such as “Abortion is violence,” “Abortion is genocide” and “Abortion is not healthcare,” were rejected by the billboard company. Others, such as “Abortion is lost fatherhood” and “Abortion is systemic racism,” made the cut.

The numbers from sources such as the Guttmacher Institute, former research arm of Planned Parenthood, and the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, reveal what black pro-lifers have been saying for years about the abortion industry’s eager reach into poor minority areas.

Nationally, some 36 percent of abortions are performed on African-American women, CDC figures show, while the female population is only 13 percent black. In New York City, the abortion rate is 3.7 times higher among black mothers than white mothers.

Bomberger’s first billboard campaign featured 60 signs in the Atlanta area in 2012 bearing the message “Black Children Are an Endangered Species.” He says he told a New York Times reporter who questioned use of the term genocide, that by United Nations definitions, the practice of abortion in the black community meets four of the U.N.’s five conditions for genocide.

Those conditions are: “Killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; [and] forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Of those, only the last isn’t applicable, Bomberger says.

“I don’t know how else to describe it,” he says. “How do you describe it when in New York City, more black babies are aborted than are born?”

Writing in the Wall Street Journal last July, columnist Jason L. Riley, in an article titled “Let’s Talk About the Black Abortion Rate,” reported that between 2012 and 2016 in New York City, the city’s health department recorded 136,426 abortions performed on black women compared to 118,127 black babies born. Among whites, Hispanics and Asians in New York City, births far surpassed abortions.

Alveda King, niece of Martin Luther King Jr. and a noted pro-life activist, agrees.

King says she had two abortions in the early 1970s, the first one without her consent at the hands of a doctor early in her pregnancy. In 1983, when she says she was truly converted to Christ, her eyes were opened by some other African-American believers who were discussing abortion.

“They were talking about genocide and how abortion was one part of the genocide movement—the new genocide movement. And I was surprised, but then I began to explore it.”

Walter Hoye, a former pastor and founder of the Issues4Life Foundation in Oakland, Calif., says that between 1967, when then Gov. Ronald Reagan signed a bill legalizing “therapeutic abortion” in California, and 2014, more than 20 million black babies were aborted. Reagan later changed his mind on the morality of abortion.

“That’s 40 percent of the under-50 generation today,” Hoye says, adding that black abortion rates exceed combined death rates among blacks from heart disease, stroke and cancer. Much of Hoye’s work is dedicated to convincing black pastors the abortion issue is not about secular politics but about Biblical truth.

In the 1960s and ’70s, civil rights activists such as Fannie Lou Hamer and a young Reverend Jesse Jackson had called abortion and the larger birth control movement “genocide.” Jackson used much the same language in an often-cited Jet magazine article in 1973.

And in 1975, Jackson worked hand in hand with Billy Graham’s wife, Ruth Bell Graham, and others to support a constitutional ban on abortion through a group called the Christian Action Council.

Prior to Jackson’s 1984 presidential run for the Democratic nomination, “he departed from the Word of the Lord and took on the feminist agenda” and a pro-choice position, as King put it.

Today, King, as director of Civil Rights for the Unborn, is part of a small, dedicated band of African-American pro-life leaders working to open hearts and minds to the reality of abortion and its roots in the early 20th century eugenics movement.

The term eugenics (meaning “well-born”) was coined in 1883 by Francis Galton, a former English slaveholder, anthropologist and half-cousin to Charles Darwin. His writings were influential at a time in America when fear by white industrialists over the growing population of former slaves was at its zenith.

Galton’s ideas on human breeding flourished in the American eugenics movement, which held sway in powerful circles in the early 20th century and led to the founding of the American Birth Control League (later known as Planned Parenthood) by Margaret Sanger. Eugenics garnered a wide array of fascination—from wealthy families such as the Rockefellers, President Theodore Roosevelt, the Ku Klux Klan and the rising Nazi movement in Germany.

The stated concern of the eugenics movement was to eliminate the spread of “feeblemindedness” and the “immoral” and criminal classes, but the underlying goals, not unlike the abortion movement today, were to stall the birthrate among black Americans, Native Americans, other nonwhites and the physically and mentally disabled.

PLANNED PARENTHOOD

Much of the link between the early eugenics movement and its toll on black Americans is documented in the 2009 film “Maafa 21: Black Genocide in 21st Century America.”

However the term eugenics was spun at the time, the idea clearly appealed to many white elites, especially in the 1920s and ’30s, as well as some anti-immigrant groups and the re-emerging Klan movement, which ballooned in popularity in the 1920s in the South, West and Midwest.

Writing in the Birth Control Review in 1922, Sanger said: “We are paying for and even submitting for the dictates of an ever-increasing [and] unceasingly spawning class of human beings who never should have been born at all.”

Sanger’s colleague at the American Birth Control League, T. Lothrop Stoddard, was even more blunt, referring to the “Asia peoples,” “American Indians and the American negroes” as “barbarian stocks” that needed to be excluded from America. Adolf Hitler and Heinrich Himmler, who led the Nazi eugenic efforts during the Holocaust, relied on counsel from Stoddard and the writings of American eugenicist Madison Grant, whose book “The Passing of The Great Race” Hitler considered “my bible.”

By 1942, with a growing knowledge of the Nazis’ use of eugenics, the American Birth Control League, led by Sanger, made a calculated marketing decision, changing its name to Planned Parenthood. Sanger’s three-year-old “Negro Project” to sell the idea of population control in black communities continued with modest results for three decades, with strong resistance from most civil rights leaders, who were suspicious of white elites pushing birth control. In as many as 30 states, even as late as the early 1970s, thousands of black females, including many teenagers, were sterilized by state-run “eugenics boards,” often without consent, if they were deemed feebleminded or incapable of raising children.

Consequently, groups like Planned Parenthood, which had struggled to develop a strong rapport with black gatekeepers, welcomed the advent of legal abortion as a new strategy.

“The legalization of abortion was so crucial for the eugenics movement,” Mark Crutcher of Life Dynamics says in the “Maafa 21” film. “Legalization gave the ability to market abortion in the black community, and from a eugenics standpoint, that changed everything.”

After the Roe v. Wade court decision federally legalized abortion, it began gaining wider acceptance in the black community. As white and Hispanic abortion rates have declined over the last 40 years, black abortion rates have swelled, helped along by U.S. government funding to Planned Parenthood and United Nations population programs, and support from both Republican presidents such as Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford and Democratic presidents Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama.

Hoye, the former California pastor, says the solution, ultimately, is not in politics but in the church—and specifically in the pulpit. With years of sidewalk counseling experience, he says pregnant women in dire straits want to know three things: “Does God love me? Does God love my baby? Will you help me?”

“We can’t afford to not talk about this in our churches,” Hoye says. “We can’t have black women who are in our churches bump into a preacher on a public sidewalk asking the question, does God love me? Does God love my baby? She should already know that. She should already know what the Bible clearly teaches.”