A knock on Tony Dungy’s door at the Stanford Court Hotel in San Francisco sent his heart racing.

On the other side of that door on that afternoon of Feb. 6 was the answer to his burning question: Would he be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s class of 2016? This was his third year of eligibility and his third year as a finalist. Dungy, former head coach of the Indianapolis Colts and Tampa Bay Buccaneers, had been asked to wait at the hotel while the Hall’s 46-member board of selectors met privately to deliberate and vote. Seventeen other finalists also waited.

David Baker, president of the Hall of Fame, stood at the door—smiling. “It is my great pleasure to tell you … that you are going to Canton,” Baker said, referring to Canton, Ohio, where the Hall is located. He extended his arm to shake Dungy’s hand; then, pulling Dungy into an embrace, he said, “God bless you, Coach. God bless you.”

Dungy celebrated with his wife, Lauren, and he prayed: “Lord, thank You for this special honor. It’s probably the last sports honor I’m going to get. I’m very gratified, but I want to utilize this like I have everything else in my career—I just pray that it will point people to You.”

On Aug. 5, the day before the Hall’s formal enshrinement ceremony in Canton, Baker said Dungy’s honor heralds “the beginning of a whole new relevance for Tony Dungy because his first name for the rest of his life will be ‘Hall of Famer’ Tony Dungy. Because of that, there’s an opportunity for him to reach more people in a way that a presidential candidate might not even get.”

In an interview with Decision, Dungy said he looks back and sees God’s hand mightily upon his life and career during what he considers an unlikely journey to the Hall of Fame.

“It’s amazing how God directed me in the right paths and put the right people in front of me for this to happen,” he said.

One of those people was Leroy Rocquemore, the junior high assistant principal who talked Dungy out of quitting the Parkside High School football team in Jackson, Mich., over a dispute with the head coach during his senior year.

“I hadn’t seen Mr. Rocquemore in two or three years when he called me up and said, ‘You need to come to my house because word on the street is you’re not going to play,’” Dungy said.

“He talked me into apologizing [to the coach] and getting back on the team. Who knows where I would be now if he hadn’t done that? I don’t know what I’d be doing, but I know I wouldn’t have been a football coach in the NFL.”

In 1977, upon signing with the Pittsburg Steelers as an undrafted rookie, Dungy met Donnie Shell, his first NFL roommate. Shell helped Dungy, a quarterback in college, learn how to play the defensive safety position.

“I kind of became joined at the hip with Donnie because of learning the new position and the fact that he was probably the most on-fire Christian guy I had ever met at that point in time,” Dungy said.

Dungy had accepted Christ as a young boy, but had never truly surrendered his life to the Lord. In fact, in high school and college, he was nothing like the mild-mannered, self-controlled man who’s been one of the NFL’s most beloved figures for at least two decades.

“My high school buddies laugh like crazy when people describe me as cool and calm,” Dungy said. “Back then, I was ultra-competitive and hot-headed. I was the guy who got thrown out of games and was given technical fouls in basketball.”

After meeting Shell, all of that began to change, particularly after Shell confronted Dungy during the Steelers’ ’77 training camp. Dungy was stressed out, Shell recalled.

“He really thought he wasn’t going to make the team,” Shell said. “I saw the concerned look on his face. And I said, ‘Well, you know, maybe in this instance you’re putting football before God and before the things He wants you to learn from what you’re going through.’”

Dungy was halted.

“He stroked that long chin of his and said, ‘Man, I never thought about that,’” Shell said. “His testimony about that is in the first book he wrote, about how that moment turned his life around spiritually and helped put his priorities in order.”

Dungy became an assistant coach after playing only three NFL seasons. He eventually wound up in Minnesota, where he spent four seasons (1992-95) as defensive coordinator.

That’s where he met Minnesota Vikings chaplain Tom Lamphere.

“From the very first day I got there, Tom talked about serving the Lord,” Dungy said. “He would always say, ‘You’re going to have a chance to do something someday that speaks for the Lord, and you need to be prepared.’”

Lamphere led Dungy in a yearlong study of the Book of Nehemiah. Every Monday they would meet and study. Lamphere told him, “This is the best book on leadership, and you’re going to need to fall back on this.”

Lamphere also counseled Dungy through his repeated failures at landing a head coaching job. Though Dungy’s Vikings’ defense ranked No. 1 in the NFL in 1993, he didn’t even receive an interview for a head coaching position. Interviews in subsequent years spawned rumors that perhaps he was too nice and mild-mannered to be a head coach.

“Tom was right there to say, ‘Don’t worry about that,’” Dungy said. “Do your job the best you can do, and let the Lord make the decision on the next step.’”

Dungy’s opportunity came in 1996 when he was hired by the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Though he led them from obscurity to post-season prominence, his tenure ended after six seasons and a difficult playoff loss.

He was unemployed for less than a week. The Indianapolis Colts hired him as head coach and paired him with star quarterback Peyton Manning and super-astute general manager Bill Polian, a 2015 Hall of Fame inductee.

The Colts made the playoffs all seven seasons Dungy coached, and in 2007 he became the first African-American head coach to win a Super Bowl.

The season before the championship, he and Lauren endured the agony of losing their 18-year-old son, James, to suicide.

“Something like that tears you apart, but you understand that God is still there,” Dungy said. “In 2 Corinthians (1:3-7), Paul says when we have trouble, God comforts us, and the reason He does is so we can comfort other people. I think that’s what’s happened with me. I’ve seen so many people come to my aid and our family’s aid, and now we’ve been able to do that for other people. That’s been pretty awesome.”

Dungy’s example of faith lived out, even in tragedy, has touched the lives of countless numbers of people over the years, especially the players he not only coached but also mentored.

One of his best players, former Colts receiver Marvin Harrison, was inducted into the Hall of Fame with the same class as Dungy. During part of his speech at the Aug. 6 induction ceremony in Canton, Harrison turned toward Dungy and spoke directly to his ex-coach.

“I could sit up here for 10 [or] 15 minutes and tell you about how important it was to have you as my coach,” Harrison said. “You taught us how to be teammates. You taught us how to be men. But the most important thing you taught us was about fatherhood.”

About an hour later, during Dungy’s speech, he asked all of his former players who were assembled to stand so he could honor them. “There’s no doubt these guys are responsible for me being up here today,” he said. “I thank you guys. I love you, every one of you.”

Tears welled up in Dungy’s eyes.

“The Lord has truly led me on a wonderful journey,” he said, in closing his speech.

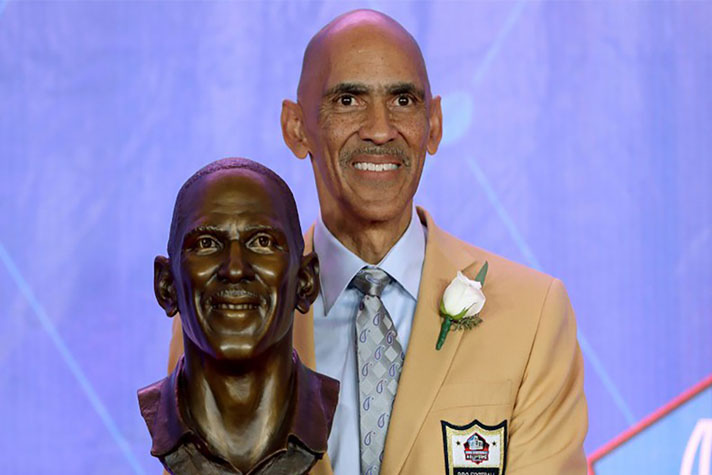

As with all the former NFL greats who are enshrined, a bronze bust of Dungy’s likeness has been permanently placed in the Hall’s prestigious gallery.

“I’m told that the bronze bust of Tony will last 40,000 years,” said David Baker, the Hall’s president. “But there is a Hall of Fame in Jesus Christ that will make 40,000 years look like a blink of an eye.”

©2016 BGEA