Note: In honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Decision is reposting this article from the 2018 Billy Graham memorial issue that was published after his passing. Our hope is that Mr. Graham’s heart for racial harmony will encourage readers today to take to heart the Biblical mandate to rise above the racial strife that continues to plague the world.

Long before President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Billy Graham was a leader in civil rights, holding integrated meetings and personally walking from the pulpit to pull down the ropes that separated the races.

He said it so many times in his Crusades: “If you don’t remember anything else I say, remember this—God loves you. God loves you. God loves you.”

Billy Graham intended that message for all people, regardless of race. And not only did he preach it, he lived it. He never wavered from his calling to be an evangelist, but in his evangelism, he helped foster racial harmony, cooperation and reconciliation.

In the early 1950s—before the Supreme Court ruled segregation in public schools unconstitutional—Billy Graham took a personal stand during his Crusade in Chattanooga, Tennessee. When Mr. Graham arrived at the meeting site, he saw that the local committee had roped off the seating into sections that would keep blacks and whites apart. Mr. Graham personally pulled down the ropes and refused to let local leaders put them back up.

“I decided that I would never preach to another segregated audience,” Mr. Graham said later.

In 1956, Billy Graham made a plea in Life magazine for an end to racial intolerance, placing it firmly as a Gospel imperative: “The church, if it aims to be the true church, dares not segregate the message of good race relations from the message of regeneration, for the human race is sinful—and man as a sinner is prone to desert God and neighbor alike.” He reminded readers, “The Bible also teaches that justice and mercy are two qualities which shall be taken into account at the Great Judgment.”

Mr. Graham strove for racial harmony in spite of opposition. In 1957, when his Madison Square Garden Crusade was drawing mostly white crowds, Mr. Graham sought advice from Howard Jones, a black pastor and evangelist from Cleveland, Ohio. Jones, who had served churches in New York and knew many other pastors in the area, told Mr. Graham: “If blacks aren’t coming to your meetings, you need to go to where they are.”

When Mr. Graham asked him to explain, Jones said: “Go to Harlem!”

Over the protests of some of his white supporters, Mr. Graham took Jones’ advice. Thousands turned out for meetings in Harlem and in Brooklyn, and hundreds received Christ. Mr. Graham invited them to come to Madison Square Garden.

“Because Billy had gone to where the black people were, the blacks began to attend the Crusade meetings,” Jones said. “What’s more, Cliff Barrows asked Ethel Waters to sing at the Crusade, and she sang in the choir every night. One evening Cliff asked Ethel if she would do a solo. When she sang His Eye Is on the Sparrow, it brought the house down.”

Still, when some whites heard that Jones was joining Billy Graham’s Team as an associate evangelist, they objected and threatened to withhold financial support. Mr. Graham did not back down. He told Jones: “I don’t care what they say, Howard. I’m going through with this if you’ll go through it with me.”

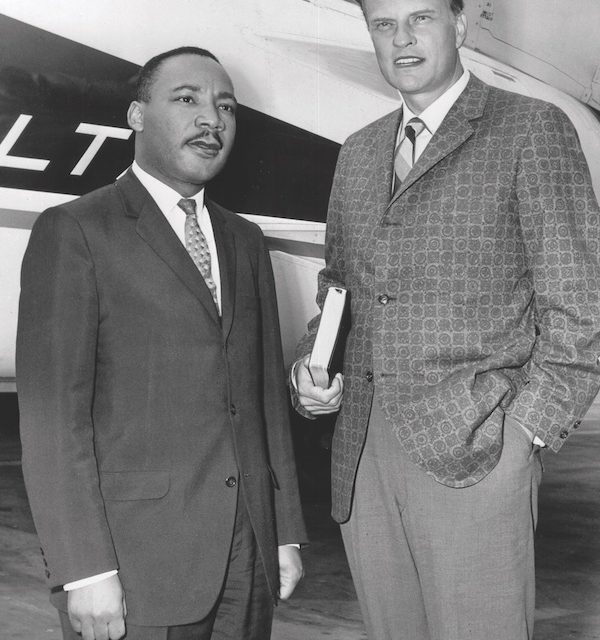

Mr. Graham also invited Martin Luther King Jr. to address his Team on the subject of racial integration and to offer a prayer during the New York Crusade. The two developed a warm friendship. In his autobiography, Just As I Am, Mr. Graham recalled: “Early on, Dr. King and I spoke about his method of using nonviolent demonstrations to bring an end to racial segregation. He urged me to keep on doing what I was doing—preaching the Gospel to integrated audiences and supporting his goal by example—and not to join him in the streets. ‘You stay in the stadiums, Billy,’ he said, ‘because you will have far more impact on the white establishment there than you would if you marched in the streets.’ … I followed his advice.”

King once said, “Had it not been for the ministry of my good friend Dr. Billy Graham, my own work in the civil rights movement would not have been as successful as it has been.”

As racial unrest increased in the mid-1960s, Mr. Graham again took a stand for integration during his 1964 Crusade in Birmingham, Alabama. The city was a tinderbox of tension following the previous year’s bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church, in which four black school children were killed.

Crusade billboards showed a black silhouette of Mr. Graham, which prompted segregationists to splatter paint on many of the signs. The state police, fearing violence, provided protection for Mr. Graham and the Team. But in spite of the fears, the meetings at Legion Field Stadium went on as scheduled and became the first integrated meetings ever held in the city.

In 1965, Mr. Graham invited Ralph Bell, a black pastor at West Washington Community Church in Los Angeles, and chaplain at the Los Angeles County Jail, to join his Team as an associate evangelist. Bell’s 39-year ministry in prisons on behalf of Mr. Graham, as well as Bell’s own Crusades, led many thousands to faith in Christ and further communicated Mr. Graham’s belief that there are no racial barriers at the foot of the cross.

The insidious issue of segregation that Mr. Graham fought so arduously at Crusades in the U.S. also reared its ugly head overseas. In South Africa, he encountered a nation ruled by apartheid, a strict policy of segregation that caused Mr. Graham to rebuff several invitations to preach there. But God was clearly working behind the scenes, because BGEA friend Michael Cassidy, founder of Africa Enterprise, was able to gain government permission to hold a fully integrated evangelism conference and evangelistic rally.

So in 1973, Mr. Graham traveled to Durban. And while the nation’s future president and Nobel Peace Prize winner Nelson Mandela was imprisoned on Robben Island, Billy Graham spoke out on behalf of black South Africans.

During a press conference, Mr. Graham looked directly into the TV cameras and declared that apartheid was sin. Newspapers the next day blared such headlines as “Billy Graham: Apartheid Doomed.”

And God blessed Mr. Graham’s outreach. At his March 17 rally in Durban, he preached to a packed, multiracial crowd of 45,000 people, with some 3,300 people making spiritual decisions. The following week in Johannesburg, a crowd of 60,000 broke a previous stadium record, and 4,000 people committed their lives to Christ.

Twelve years later, a black church leader in South Africa said, “The spirit of reconciliation we today sense in many hearts of South Africans can be traced directly back to the Billy Graham meetings held in Durban and Johannesburg in 1973. He was the one who demanded total integration for all of his meetings. And it was done. … From that moment on, we were on the road to reconciliation.”

Billy Graham recognized that true reconciliation could come only through changed hearts. When people came forward in the Crusades to commit their lives to Christ, Mr. Graham often issued a challenge to them to reach out to people of other races.

Even Crusade preparations helped foster racial harmony. During the 1999 Indianapolis Crusade, the local Crusade leadership, believing that racial reconciliation was the region’s most pressing issue, mandated that each of the Crusade’s working committees be led by two co-chairs, each of a different race.

Ten years later, Edwin J. Simcox, who chaired the Crusade’s executive committee, reflected: “There were personal friendships among African-American and white pastors, as well as lay people, that were forged in the campaign and have remained to this day.” ©2018 BGEA

Photo: BGEA Archives